The Head of Karl Marx | Plastics Comrade? | End of the Sixties

| Alchemical Wedding at the Royal Albert Hall

There was that sudden, reluctant awakening in the dead of night, knowing that something in the outside world had intruded into my dreams and was jolting me from the deep sleep of youth. I shifted in my bed. Blurry explanations began their sluggish way into my rousing consciousness and were sorted for consideration.

There was that sudden, reluctant awakening in the dead of night, knowing that something in the outside world had intruded into my dreams and was jolting me from the deep sleep of youth. I shifted in my bed. Blurry explanations began their sluggish way into my rousing consciousness and were sorted for consideration.

What was it this time? Another fiery car crash at the bottom of Highgate West Hill?

The dangerously steep, narrow and curvy main road leveled out abruptly next to Cavours Hardware Shop where it intersected with Swains Lane, before it continued on south as the sedate Highgate Road. My view from the second floor window of our family’s maisonette strategically overlooked a bus terminus and that perilous intersection beyond, which had periodically claimed so many lives.

Perhaps it was the thundering hooves of one hundred horses of the Queen’s Horse Guards’? With a uniformed cavalry rider on one horse and running a second horse alongside by its reins, the sinuous pairings regularly galloped by my window. Two

abreast they would surge forward on their regular, rain-or-shine, pre-dawn exercise

through the deserted North London streets. Clattering past, they would continue to the north, audibly slowing up heart-straining Highgate West Hill. The staccato sounds would gradually fade away into utter silence. I always wondered if they watched for out-of-control cars coming down the other way.

Or was it Karl Marx again?

Out of long habit, I got out of bed, staggered in the dark to the window and pulled aside first the heavy streetlight-blocking curtain and then the diaphanous nylon lace curtain. In my sleep-groggy state I stared out at the surprisingly empty street quietly illuminated at regular intervals by blotchy yellow sodium light. I saw no finely trained Arab steeds, their coats glistening with sweat, streaming by my window. Nor did the image of a mangled automobile engulfed in flames painfully strike my nighttime eyes.

So it had to be Karl.

The recent bizarre poisonings of Putin-dissenters brought to mind my life in London in the early 1960’s and my brush with Soviet spies. I lived near Highgate cemetery where the main polonium-laced dissenter was interred, just a Molotov-cocktail’s throw from the imposing grave of Karl Marx.

The recent bizarre poisonings of Putin-dissenters brought to mind my life in London in the early 1960’s and my brush with Soviet spies. I lived near Highgate cemetery where the main polonium-laced dissenter was interred, just a Molotov-cocktail’s throw from the imposing grave of Karl Marx.

At the age of eleven, I knew little of global matters, but one day they came right by my front door. Playing with friends in our maisonette’s front yard, I was startled by the dramatic appearance of many large, black, soviet Zil limousines turning onto our street. All of their bulbous front fenders were sporting a small fluttering red flag bearing a yellow hammer-and-sickle motif. A flatulent posse of police motorbikes caught up with my ears. With closed black windows, the cars sped smoothly past my gaping mouth.

Having recently moved into the flats I didn’t know what was happening. William, my next door neighbor, apparently a veteran of this ominous spectacle, leapt into action and shouted “Let’s go!” He and three other boys raced out of the yard and into the street following the cars. I ran after them, not knowing why or what our fate would be at the end of our adventure.

The narrow road and the amount of traffic caused the caravan to slow, so we gained some ground. Between gulps of air, as we raced up the hill I asked what was happening.

William snorted “It’s bound to be sum big Russki commie leader.”

“Why are they coming here?” I panted.

“coz Karl Marx is buried ´ere, aint ´e!” he wheezed back.

“Who’s Karl Marx?”

“‘e’s the bloke who invented communism aint ‘e!” he said derisively from the height of his eighteen-month age advantage.

Up ahead the police had cordoned off the road, so we bunked each other over a brick-and-cast-iron spiked wall and descended into the ghostly dense underbrush of an old cemetery. Lost, I followed the other boys on the narrow dark paths, hoping they knew where they were going. Old tombstones creaked at all angles as fanciful souvenirs covered with moss and ivy watched my passage. Crashing through a hedge we emerged onto a sunnier, wider, gravel path.

For me, the end of that magical time really was sealed early on the evening of October 4th in London in 1970. On the way from my flat across the road from the notorious Mangrove Cafe in Ladbroke Grove, to my parent’s house at Parliament Hill Fields, I emerged from Kings Cross Station to catch a 214 bus. At the corner of Kings Cross Road and Euston Road was a makeshift newspaper kiosk huddled against the entry steps and the fluted columns of the superb Victorian folly of St. Pancras Railway Station. In front of the kiosk I saw large black headlines on the white Evening Standard teaser board. The thin, transient paper edges were flapping in the gentle breeze through the wire holding frame. ‘Famous Woman Rock Singer Dies’. Oh dear, who was it now? So many had crashed and burned since the onset of the Beatle-led cultural revolution in 1962. Reluctantly, but inexorably, I walked over to the kiosk and looked down at the tabloid-size newspapers piled neatly on the counter.

For me, the end of that magical time really was sealed early on the evening of October 4th in London in 1970. On the way from my flat across the road from the notorious Mangrove Cafe in Ladbroke Grove, to my parent’s house at Parliament Hill Fields, I emerged from Kings Cross Station to catch a 214 bus. At the corner of Kings Cross Road and Euston Road was a makeshift newspaper kiosk huddled against the entry steps and the fluted columns of the superb Victorian folly of St. Pancras Railway Station. In front of the kiosk I saw large black headlines on the white Evening Standard teaser board. The thin, transient paper edges were flapping in the gentle breeze through the wire holding frame. ‘Famous Woman Rock Singer Dies’. Oh dear, who was it now? So many had crashed and burned since the onset of the Beatle-led cultural revolution in 1962. Reluctantly, but inexorably, I walked over to the kiosk and looked down at the tabloid-size newspapers piled neatly on the counter.

My heart sank down to my plimsolls. “Not her! No! Not Janis!” The bored newspaper seller ignored my outburst as I gave him the sixpence. The

bad/great girl of rock, the singer whom many of us guys secretly wanted to take in our arms and protect her from the world that was eating her up; was dead. Janis was just another rock-star cliché in the end. Her immense talent and future wasted, the potential barely tapped, just like the youth movement she helped define and inspire. Even uber-smashed Lady Day had left a substantial catalogue for us to regret over. Watching Janis Joplin cry, laugh, emote, and live through each song she sang had always given me a spine- tingling experience like no other performer. Her voice seemed to split into a chorus of separate, different voices when she screamed with pain and then softly sighed with love for us all. I never saw her perform live, missing her at the Royal Albert Hall on her only tour in 1968, but was captivated by her on the Monterey Pop film, and some other contemporary TV shows she appeared in. Certainly, not a typical beauty; she had bad skin, drank and smoked too much, but her inner vulnerability gave her a powerful outward glamour. I played her vinyl albums hard to their scratchy end, just like Janis herself.

Having just turned twenty, it was getting hard to hold onto the idealistic dreams of the late sixties with our heroes dying, or being imprisoned almost daily. Governments feared the growing youth movement, they, the Churches, schools, or parents had no control over. The old-system of ‘keep quiet’ conformity was not working anymore with many of my generation. The awakening information age now showed us all we needed to know about how the world was being run, and by whom. The lurid moral turpitude and revolutionary spirit seen by the powers-that-be, branching out from this growing awareness, had shocked the establishment to its calcified roots, and as usual reared back with harsher laws, brutality, and fewer civil liberties.

THE ALCHEMICAL WEDDING AT THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL

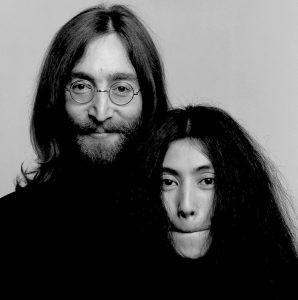

John & Yoko, Bagism, and the Naked Lady

18th December 1968 – 55th year anniversary – 12/13/23

1968, what a year. Vietnam, Nixon, Woodstock, Altamont, and in December, in London, the Alchemical Wedding to top it all off! I was eighteen and reveling in the post-1967 Flower Power revolution emerging from San Francisco, and which had spread to the streets of London where I gingerly walked barefoot and be-fringed to happenings and festivals.

1968, what a year. Vietnam, Nixon, Woodstock, Altamont, and in December, in London, the Alchemical Wedding to top it all off! I was eighteen and reveling in the post-1967 Flower Power revolution emerging from San Francisco, and which had spread to the streets of London where I gingerly walked barefoot and be-fringed to happenings and festivals.

It was mid-December, and Rich Abrash, an American friend from New York, showed up for a visit. Rich was studying anthropology in Paris to avoid the US draft. My friend Jeffrey Schwarz and I had met Rich in Paris in June, when the cobblestone streets were still torn up from the rioting students of May. He’d got word that an event called “The Alchemical Wedding” was going to happen, at The Royal Albert Hall of all places!

The London Arts Lab had booked and organized the event (under the supposed official respectable auspices of Leonard Cohen, and many of the young artists, intelligentsia and hippnessians of London had planned a wild underground hippie showcase for the alternative arts and music community of the time. Posters had been designed by The Arts Lab, and full-page ads appeared in the main underground newspapers International Times (IT) and Oz.

The Arts Lab, housed in a Dickensian building on Drury Lane in Central London, was then the magnet for British counterculture. Founded by Jim Haynes, Hoppy Hopkins, and American activist Jack Moore, along with a street theatre group the Human Family, The Lab provided a space for any type of Art, including experimental theater, dance, art, film, music, and street performance.

On any given day you might wander in and see David Bowie rehearsing dance moves, or John Lennon popping in to see how his arts patronage was faring. Jeffrey and I used to go to the Drury Lane Arts Lab quite often during 1967 and 1968, as the food and drink was inexpensive, and the shows were cool and mostly free.

As we took our seats in the Royal Albert Hall on December 18th, we could see that word of the event must have gotten out quite well, as the place looked close to four thousand holes full. Fashions ranged from grubby denims to outlandish and colourful hippy garb. Cigarette smoke, and an occasional whiff of hash wafted through the hall, along with a good dose of patchouli incense. Jeffrey and I were on the lower level, in the middle of a row, about eight rows from the front, stage right. Rich’s ticket took him elsewhere.

Our “Beatle senses” kicked into immediate high gear, when we espied John Lennon and Yoko Ono, both dressed in dark clothing, with Lennon in a denim jacket, taking their seats below us to the left, in the well of the main floor. A seat neighbour pointed out Ken Kesey and some of his Merry Band, were sitting with the iconic couple…